GSW Website Search

- Apply

- About

- Academics

- Admissions

- Financial Aid

- Athletics

- Student Life

- myGSW

- A-Z Index

- Directory

- Map

- Visit

- Give

Author Note: D. Jason Berggren is a professor of political science at Georgia Southwestern State University. As part of the Americus Times-Recorder’s historical coverage of Jimmy Carter, this article was originally published in the June 21, 2023 print edition.

Article Notes: The article and the accompanying images are dedicated to honor his memory, his lifelong commitment to public education, and his regular involvement with Georgia Southwestern State University (GSW).

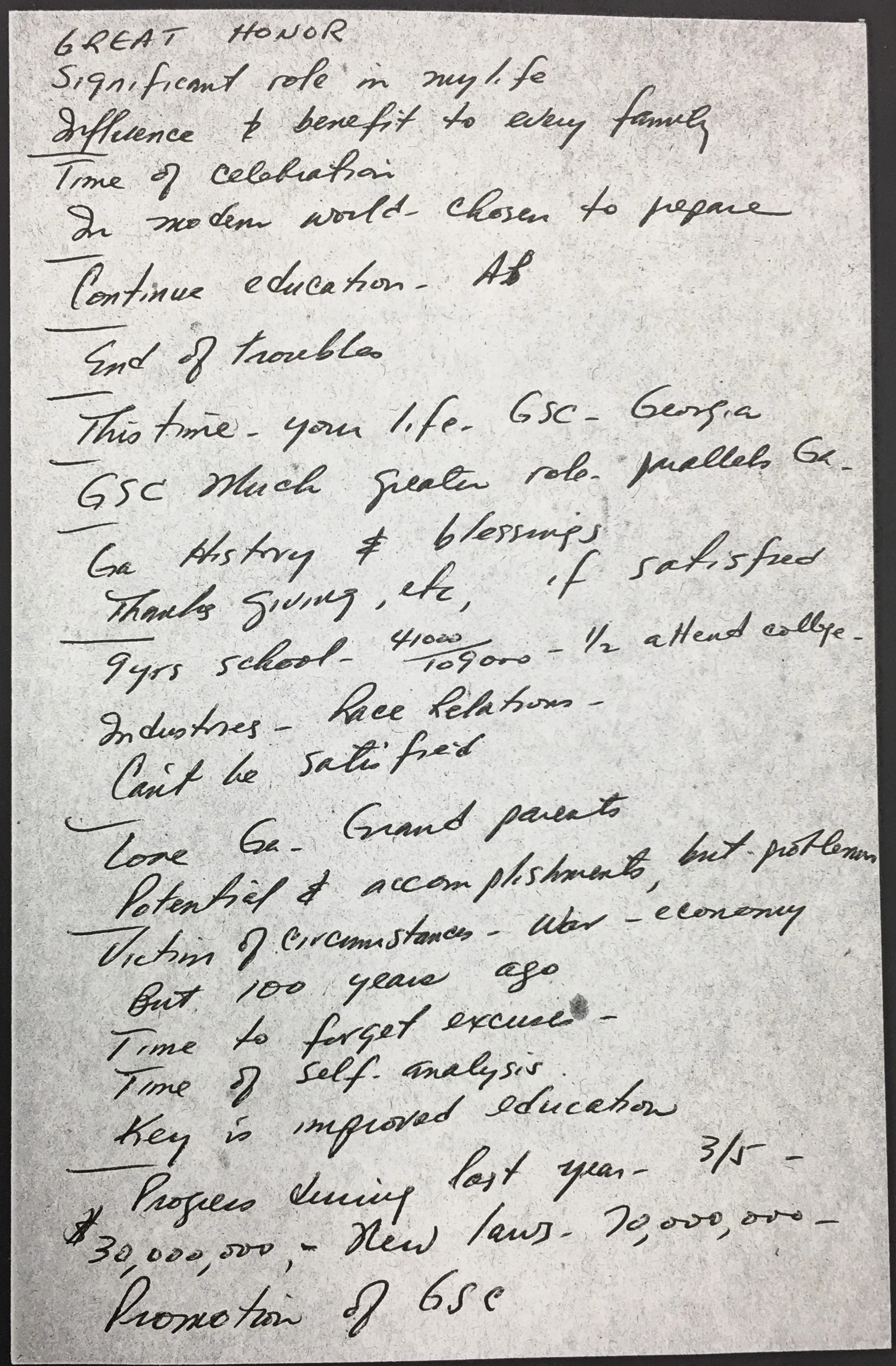

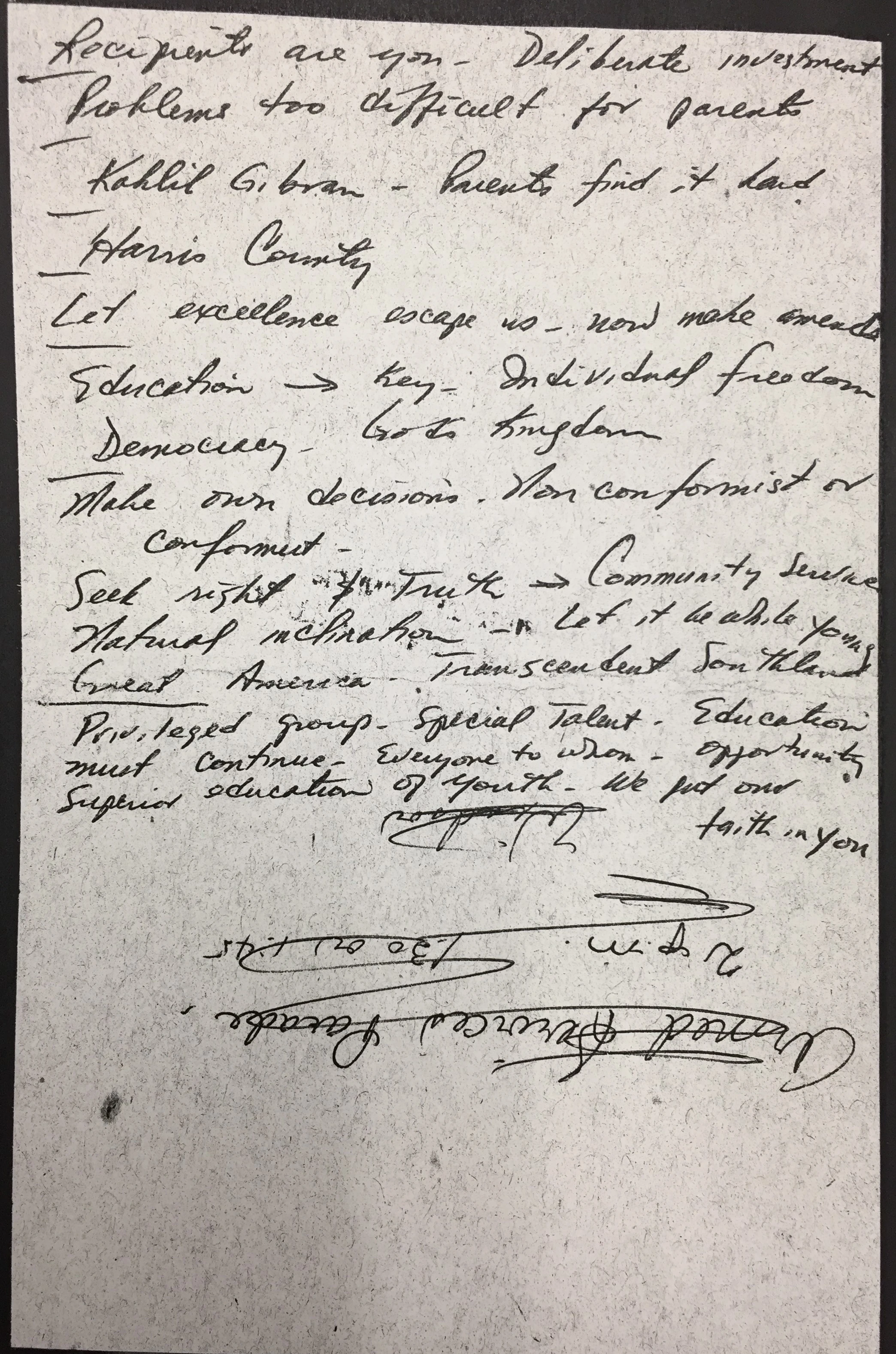

In 1964, Carter, a first-term state senator, was invited to give the commencement address at Georgia Southwestern College (GSC). His commencement involvement was confirmed with the GSW Office of Alumni Affairs in 2023. At the time, GSC was still a two-year school, but it had been promoted to “a senior college” just months before the June graduation. With a few edits, a transcript of Carter’s speech is provided here.

What is significant about this speech is that it may contain Carter’s first documented public pronouncement on race relations and the need for change. He asked the local crowd that day, “Can we be satisfied to ignore the unsolved issue of race relations, perhaps the greatest obstacle to the solution of our other problems?” The answer was no.

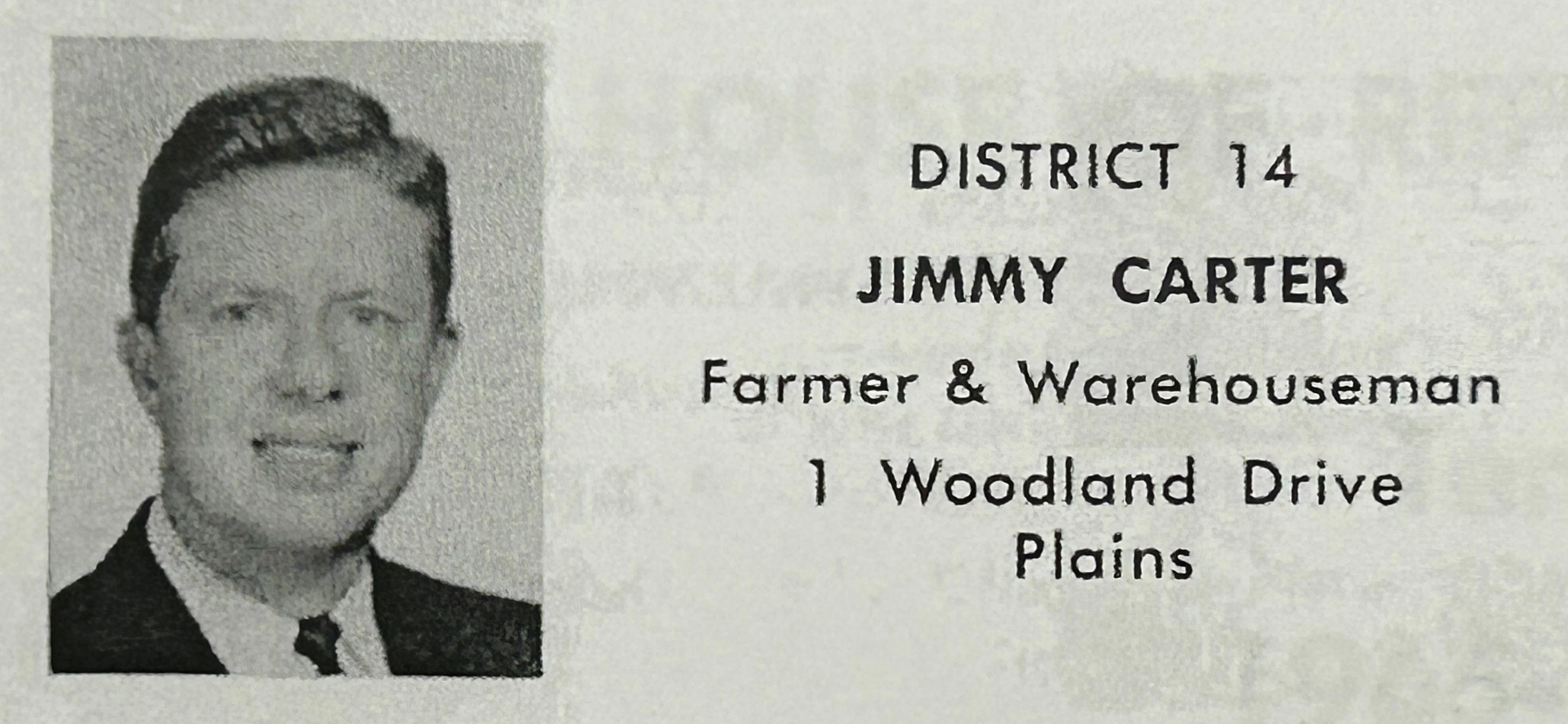

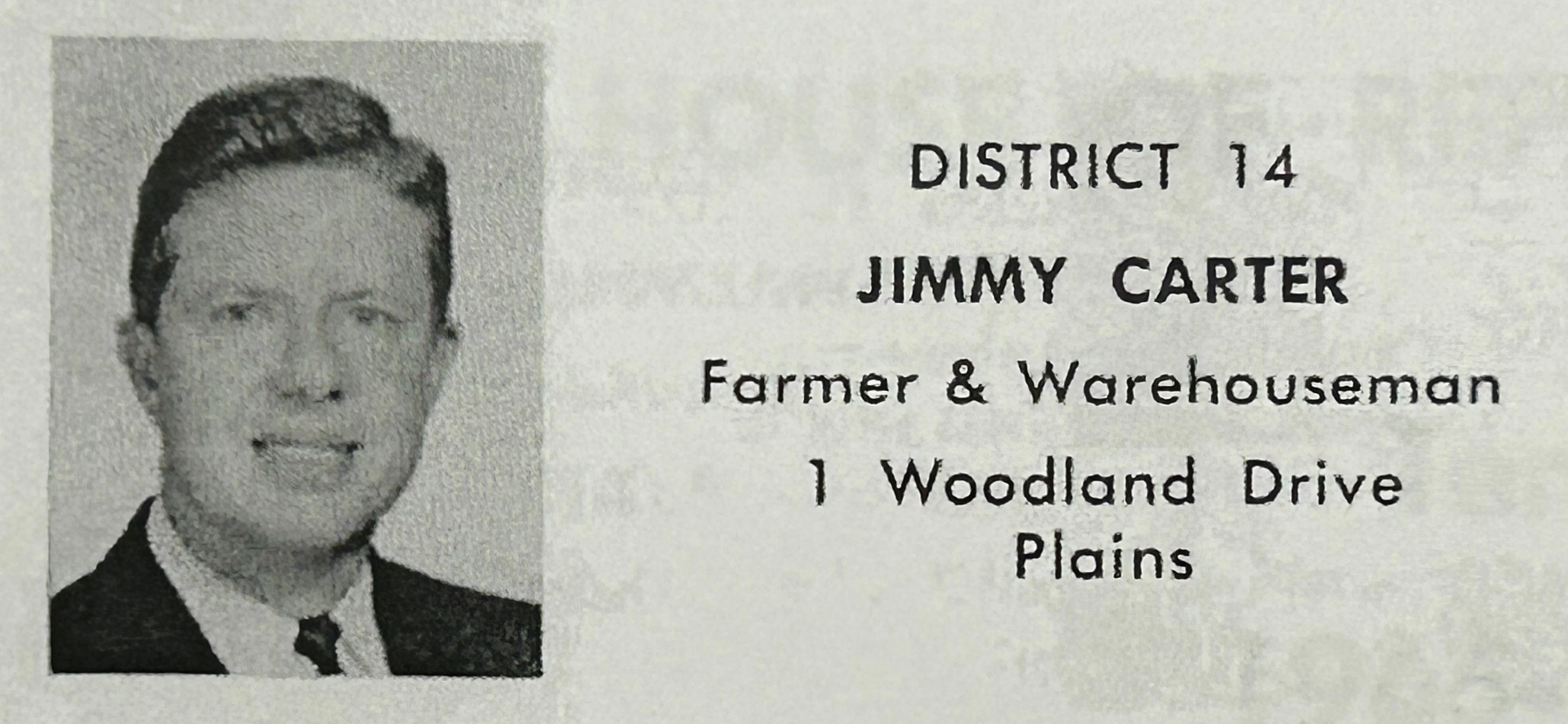

Jimmy Carter was a proud alumnus of Georgia Southwestern State University, and so was Mrs. Rosalynn Carter. In school directories, he is recognized as a member of the class of 1943 and she as a member of the class of 1946.

Before moving on to Georgia Tech in 1942 and the U.S. Naval Academy in 1943, Carter attended Georgia Southwestern for one school year (1941-1942) when it was a two-year school. Hewanted to go Annapolis, but he was unable at that time to secure a nomination from his U.S. representative, Stephen Pace, Sr. It was suggested that he enroll at the local junior college to enhance his academic credentials.

In his book, An Hour Before Daylight, Carter noted that he lived in a campus dormitory. He wrote, “In September 1941, I left home and moved into the dormitory at Georgia Southwestern College in Americus, where I concentrated on subjects that were recommended in the Annapolis guidebook for prospective midshipmen.” His dorm room was in Terrell Hall. The male-dormitory building, however, no longer exists; the site is now a parking lot for faculty and staff.

Over the years, Carter had many interactions with Georgia Southwestern. There have been graduations, dedications, birthday celebrations, and other school and community events. One notable instance was during his first two-year term as a Georgia state senator. In 1964, Senator Carter was invited to deliver the commencement address. The graduation ceremony was held on Friday, June 5, at the school’s outdoor lakeside amphitheater. According to Mildred Tietjen’s book, A Century of Achievement, 1906-2006, this was the last graduation held at that campus location. There were about 130 graduates recognized that day.

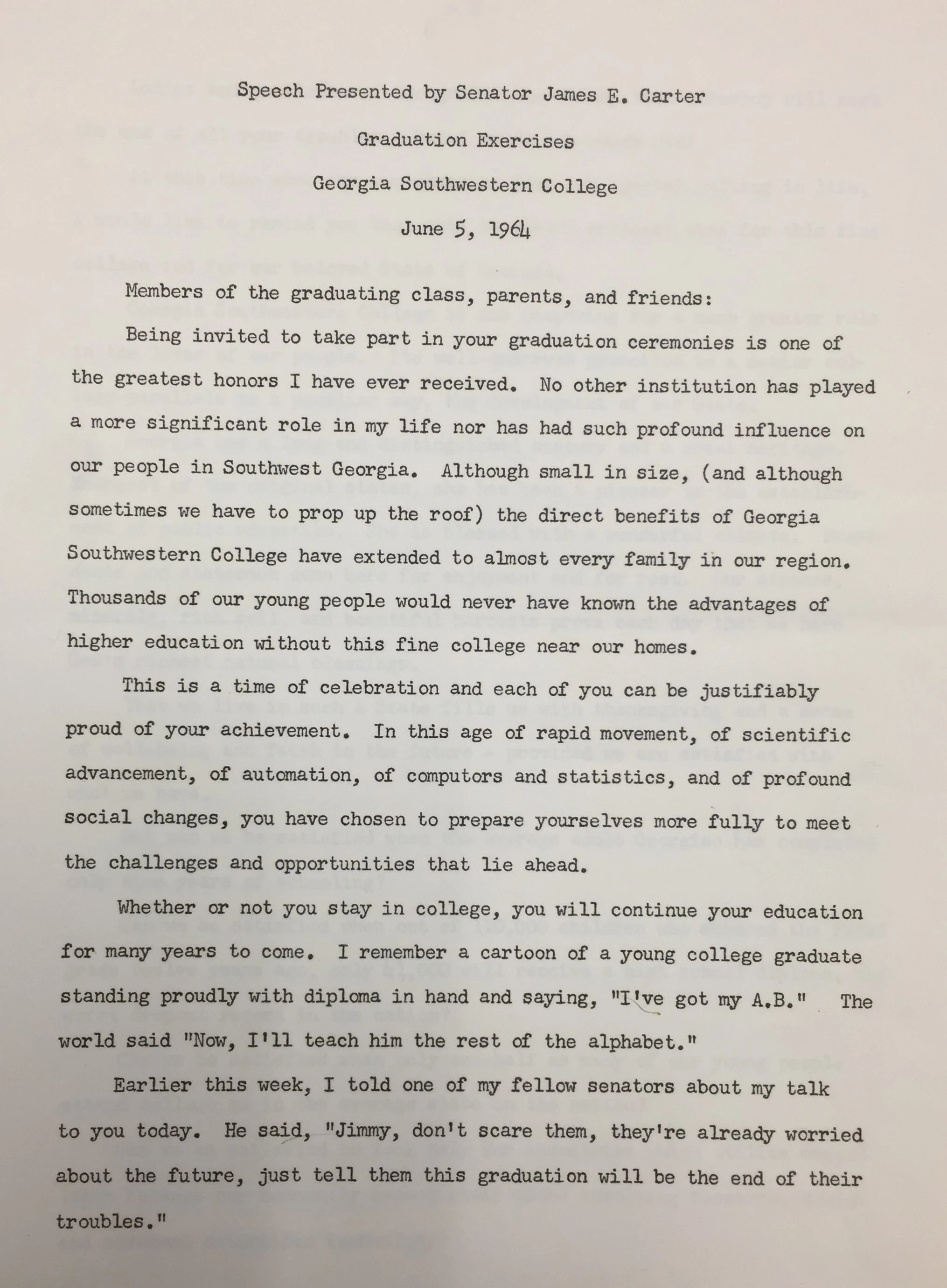

Printed here in its entirety is Carter’s prepared speech to the GSC class of ’64. Images of the handwritten outline of his speech are also included. I took these during one of my visits to the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum in Atlanta.

Carter began his remarks by acknowledging the school’s importance and its impact on southwest Georgia. In particular, he noted that many in the region would “never have known the advantages of higher education without this fine college near our homes.”

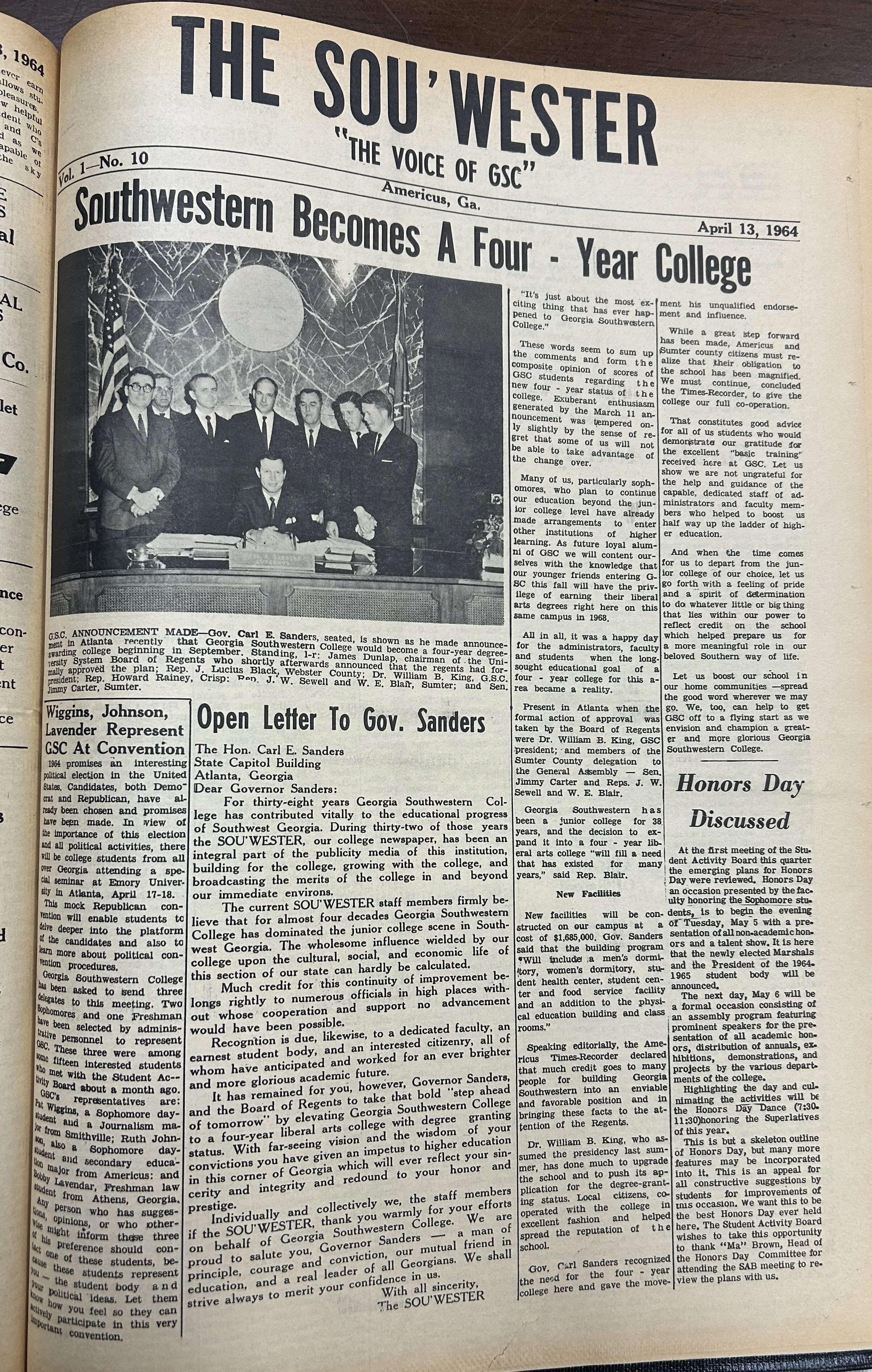

He noted the recent decision to make Georgia Southwestern a four-year academic institution. He said it was a “well-deserved promotion to a senior college.” It was one of his legislative priorities and it was a factor in his pursuit of higher office in 1966. In March 1964, he joined Governor Carl Sanders, GSC President William King, and other dignitaries for the announcement in Atlanta. Later, this would become a major issue between him and Republican congressional candidate Howard “Bo” Callaway who as a member of the University System’s Board of Regents opposed the upgrade.

Carter then expressed his love for the State of Georgia and discussed its challenges. In a series of questions highlighting some of the state’s educational problems, he rhetorically asked, “Can we be satisfied?” It was a version of his trademark question, “Why not the best?”

Next, Carter turned to race and the South’s difficult history. The scholarly consensus is that during this period of his life and political career he largely steered clear of civil rights issues and kept his real views private. His political strategy was avoidance. Doing anything more was too risky – risky for his political career and risky for his business. One noted exception to this was during a 1964 legislative special session on election reform. Carter apparently spoke before the chamber against the “thirty questions” character test used by local election officials to prevent blacks from registering to vote. It has been said that his remarks on that occasion was “his first public statement concerning racial discrimination.” However, there is no record of the speech in the official proceedings of the Georgia Senate, and it was not covered by the newspapers.

That is not the case here. In his GSC address, Carter observed how race was connected to and intertwined with a wide range of “grave” matters in Georgia and the South. Race, he averred, was “perhaps the greatest obstacle” to substantive progress for all. He said, “Can we be satisfied to ignore the unsolved issue of race relations, perhaps the greatest obstacle to the solution of our other problems?” Carter answered this question and the others he posed with a no. Although he had been accused of being a racial liberal as early as the school consolidation referendum campaign in July 1961, this public speech delivered at his alma mater may have been the clearest sign yet in his political career that he was looking beyond segregation and the politics of the past and suggesting his fellow white southerners to do the same.

Like other emerging “New South” politicians of the day, Carter argued that greater economic development and educational attainment went hand in hand with the advancement of civil rights. He asserted that white southerners should no longer blame the effects of “the War Between the States,” as devastating as it was, for their present woes. For Georgia’s senator of the Fourteenth District, “It is time for us to forget excuses and to assess – accurately and frankly – both our strengths and our failings.” While a proud southerner, Carter believed the time had come to end the “preoccupation with misfortunes of our 19th century war,” make the essential changes on race and education, and envision “an America in which our Southland can find a place of leadership.” In 1964, this was Carter’s centennial Civil War message. A decade later, for the country’s bicentennial year in 1976, this was part of Carter’s campaign message for president. As he wrote in his speech outline, this was part of his vision of a “Great America” and a “Transcendent Southland.”

Even though it had been ten years since the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled in its landmark Brown decision that state-mandated segregated schools were unconstitutional, Georgia Southwestern remained racially segregated in 1964, and it was not alone in its noncompliance. The Americus city schools and the Sumter County schools were still segregated. In fact, according to one study, only 1.2 percent of African American students across the South were in desegregated schools a decade after Brown.

On June 5, 1964, Carter stated before the GSC graduating class and their family and friends that change must come – and it was coming and imminent. A month later, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law, and in the fall of 1964, the first black students entered Americus High School. In 1966, the first black students finally entered Georgia Southwestern and Plains and Union high schools. Although he was not a civil rights advocate at that moment, Carter’s message that graduation day was clear. He said, “we have let excellence escape us” and that was unacceptable going forward.

Here is Senator Carter’s prepared address:

“Members of the graduating class, parents, and friends:

Being invited to take part in your graduation ceremonies is one of the greatest honors I have ever received. No other institution has played a more significant role in my life nor has had such profound influence on our people in Southwest Georgia. Although small in size, (and although sometimes we have to prop up the roof) the direct benefits of Georgia Southwestern College have extended to almost every family in our region. Thousands of our young people would never have known the advantages of higher education without this fine college near our homes.

This is a time of celebration and each of you can be justifiably proud of your achievement. In this age of rapid movement, of scientific advancement, of automation, of computers and statistics, and of profound social changes, you have chosen to prepare yourselves more fully to meet the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead.

Whether or not you stay in college, you will continue your education for many years to come. I remember a cartoon of a young college graduate standing proudly with diploma in hand and saying, ‘I’ve got my A.B.’ The world said ‘Now, I’ll teach him the rest of the alphabet.’

Earlier this week, I told one of my fellow senators about my talk to you today. He said, ‘Jimmy, don’t you scare them, they’re already worried about the future, just tell them this graduation will be the end of their troubles.’

Ladies and gentlemen of the graduating class, this ceremony will mark the end of all your troubles – but I won’t say which end!

At this time when you are choosing your own special calling in life, I would like to remind you that this is also a critical time for this fine college and for our beloved State of Georgia.

Georgia Southwestern College is now preparing for a much greater role in the lives of our people. Its well-deserved promotion to a senior college parallels in a peculiar way, the development of our State.

Georgia has a long and distinguished history and a great heritage. Youngest of the original states, she has been a pioneer in the establishment of public education. She is blessed with a wonderful climate. Presidents and statesmen come here for enjoyment and for rest. Our streams, minerals, rich soil, and bountiful harvests prove each day that we have God’s richest natural blessings.

That we live in such a State fills us with thanksgiving and a sense of well-being and faith in the future – provided we are satisfied with what we have.

But can we be satisfied when the average adult Georgian has completed only nine years of schooling?

Can we be satisfied when out of 110,000 children who entered the first grade twelve years ago, only 41,000 will receive a high school diploma, the worst dropout record in the nation?

Can we be satisfied when only one-half as many of our young people attend college as in the average state in the nation?

Can we be satisfied to look only for industries which utilize manual labor because our community cannot staff those involving research, design and advanced scientific technology?

Can we be satisfied to ignore the unsolved issue of race relations, perhaps the greatest obstacle to the solution of our other problems?

We can no longer afford to be satisfied with these things.

I love my home and my native state. My family has lived here for 144 years and my wife’s family has been in Sumter County since 1833. I could carry you, within a few minutes, from this spot to the graves of our grandparents who homesteaded this land early in the last century.

I appreciate its wonderful potential and its accomplishments, but we must also recognize that Georgia has many grave problems to be solved.

You may say that we are a victim of circumstances, and that we can find the cause of our shortcomings in the War Between the States. In the 1860’s, we were left with a devastated land, our people subjugated by an unfriendly government.

Our pride remained, but our economy was shackled by unfair freight rates and exorbitant interest charges, forcing our development to be slow, and torturous and agrarian in nature.

The terrible consequences of that war cannot be overestimated, but we must realize now that this war took place 100 years ago.

It is time for us to forget excuses and to assess – accurately and frankly – both our strengths and our failings. It is gratifying to know that the time of self-analysis has already come upon us. Georgians have finally realized that the key to the fulfillment of our destiny is improved education. Do not underestimate the tremendous effort now being made to improve our educational system.

During this last year, a complete assessment has been made of our academic status, and a new program for our State has been inaugurated. We are spending almost 3/5 of our total state income on education, and a new tax program, or assumed by our people, will provide an increase of $30 million each year. A complete revision of our school laws has been made. A rapid expansion of our trade and vocational schools is

under way, and a $70 million dollar building program in our university system will provide badly needed facilities for higher education. The promotion an

d expansion of the program of Georgia Southwestern College will, for the first time, give the 750,000 people of Southwest Georgia a senior college.

The recipients of all these improvements are you, the students of Georgia. This investment is deliberately made.

I tell you quite frankly that the problems outlined above are probably too difficult and too entrenched for my generation to solve. We, as a group, are often handicapped by long established habits, by skepticism and cynicism, by prejudice and lack of courage. But you can profit by our mistakes.

Listen to what Kahlil Gibran said to the parents of Orphalese: ‘And the Prophet said to them:

Your children are not your children. They are the sons and daughters of life’s longing for itself. They come through you but not from you, and though they are with you yet they belong not to you. You may give them your love but not your thoughts, for they have their own thoughts. You may house their bodies but not their souls, for their souls dwell in the house of tomorrow, which you cannot visit, even in your dreams. You may strive to be like them, but seek not to make them like you. For life goes not backward nor tarries with yesterday. You are the bows from which your children as living arrows are sent forth. The archer sees the mark upon the path of the infinite.’

We parents find it difficult to accept these words of wisdom. Yet, perhaps we can rejoice that our children belong not to us – that they have their own thoughts – and that we cannot make them exactly like us.

Following conviction in Harris County several years ago, a negro man was sentenced to be hanged. As he approached the gallows, the sheriff asked if he had a last statement to make. ‘Yes, Sir,’ he said, ‘I want to say one thing: This here hanging is sho’ going to be a lesson to me.’

Well, I hate to admit it, but like the condemned man, your parents have recognized the needs of our Southland perhaps too late to utilize fully the lessons we have learned. In spite of wonderful blessings of climate, location and nature, somehow we have let excellence escape us. Through preoccupation with misfortunes of our 19th century war and because of the dampening of our aspirations by the constant spectre of social problems, we have for many decades failed to unleash the tremendous power of superior education. But now there is a strong force in Georgia trying to make amends.

In spite of your wonderful opportunities, you must remember that education is not an end in itself, but it is the key to freedom, and individual freedom is one of the most basic and cherished of human possessions. Our democratic society is founded on individual freedom. The consummation of God’s kingdom is dependent on individual freedom. In the beginning, as you know, God very carefully decided not to control the minds of men. With education, you are free to make your own decisions, to develop your own ideas, to be a nonconformist if you choose, and to decide wisely when to conform. You can search for greater knowledge and understanding and benefit from the lessons of generations past. We do not need to produce from our colleges a group of automatons, but individuals who seek with fervor to learn what is right and true, and who are dedicated, not to economic gain, but to community service.

Your normal development will lead eventually to community service, as a councilman, or mayor, or school board member, or through work with young people or in our churches. Most of these are nonpaying jobs, and although the responsibilities and problems are great, almost every community leader is a volunteer for this work. I tell you this to prove that man has a natural inclination for service and sacrifice. Let this desire for service be expressed in you while you are young and capable and enthusiastic and still have your dreams of a greater America… an America in which our Southland can find a place of leadership. Remember that you are a privileged group, endowed with a special talent and ability. A large portion of your formal education has been completed but you must ever seek to continue learning and growing. Remember that ‘everyone to whom much is given, of him much will be required: and of him to whom men commit much, they will demand the more.’ Remember that our homeland is one of wonderful opportunity and promise, opportunity and promise that we have somehow failed to fulfill. We have realized that our master plan for the fulfillment of this promise must be the superior education of our youth; you now face a great responsibility and a greater opportunity. Without fear of disappointment, we put our faith in you.”

Note: Kahlil Gibran (1883-1931) was a Lebanese-American writer and poet. He came from a Christian family and immigrated to the United States in 1895. The quote Carter referenced here comes from Gibran’s book, The Prophet (1923).